In Seattle, A Calmness Before The 'Really Big' Earthquake Predicted In Recent New Yorker Piece

SEATTLE -- Catastrophe will befall this lovely city, with its seaside Ferris wheel and shimmering office towers rising lazily above a glittering sound. And it could happen at any moment. The Cascadia fault, which lies just 50 miles off the coast here, is primed to deliver a powerful blow to the region in the form of a massive earthquake that will level highways and buildings and incite a tsunami capable of inundating the city's downtown.

That’s the grim reality laid out in a feature by Kathryn Schulz published in the New Yorker this week. Schulz reports that the Federal Emergency Management Agency estimates as many as 13,000 people may die as a result of the disaster.

"By the time the shaking has ceased and the tsunami has receded," Schulz writes, "the region will be unrecognizable. Kenneth Murphy, who directs FEMA’s Region X, the division responsible for Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Alaska, says, 'Our operating assumption is that everything west of Interstate 5 will be toast.'"

The impending doom isn't weighing too heavily on most Seattleites, however.

“I don’t think people are really concerned about it,” Dustin van Nieulande, a park ranger at Mercer Slough Environmental Education Center in Bellevue, Washington, says. “I think it comes up as a joke more often than it’s seriously discussed.”

Seattle scientists and city planners recently told the Seattle Times that there is an 80 percent chance that a magnitude-6.8 earthquake or similar will occur here in the next 50 years and a 10 to 15 percent chance of a magnitude-9 earthquake in the same period. Those odds are disturbingly high compared to most regions of the country, and very concerning to state and federal officials given the devastation that any such earthquake could impart.

Yet, Mike Condon, owner of a coffee shop named Mike’s Community Cup in SeaTac, remains unfazed.

“I really don’t think about it,” Condon says on a break from steaming milk and packing espresso for a steady stream of regulars Tuesday. “There’s going to be catastrophes everywhere. They're going to happen.”

Condon, 58, grew up in the area and remembers when a magnitude-6.5 earthquake hit the region in 1965 -- he was walking to school and watched the bricks of his neighbor’s chimney fall off, one by one.

Condon isn’t alone in his indifference. Van Nieulande, 41, has worked as a park ranger in the area for four years and says that never once has a visitor or local resident walked through the doors and asked about the odds of a big earthquake. He grew up in Orange County in Southern California and is accustomed to living comfortably with the idea that a massive earthquake could strike at any moment. His perspective as a naturalist also dampens the threat.

“When you’re talking about geologic time, things happen in the tens of thousands or millions of years,” he shrugs.

Van Nieulande feels safe in Bellevue, just east of Seattle, but knows that certain spots of the region could be at far greater risk.

“I think the worst impact could come to areas where buildings are older, like downtown Seattle,” he says.

In Seattle’s central business district, Sam Roach admits that she is slightly more concerned. She works as the shift manager at a Starbucks in the Broderick Building on the shady corner of Second Avenue and Cherry Street, just a few blocks from the city’s waterfront.

“I feel safe where I live but working downtown, it’s scary because all of the big buildings,” she says. “I’ve seen what earthquakes can do to large buildings and bridges.”

Roach, 24, grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area. Now she lives in West Seattle, which rests at a slightly higher elevation than downtown. She frets about what would become of her friend who works on the 40th floor of the Columbia Center, the tallest building in the city and second-tallest structure on the entire West Coast, if an earthquake were to hit.

David Morgan, a 75-year-old lifelong resident who was waiting nearby for his wife and granddaughter to finish a city tour, brushes aside any fault-related concerns.

“There’s so many other things that could get me -- that’s so far down the list, it’s not even worth worrying about,” he says. “I have trouble enough worrying about the things I have some control over.”

Morgan admits that his propensity for risk may be slightly skewed. He flew 100 missions as a fighter pilot in Vietnam. At that time, Air Force policy permitted pilots to return home early if they completed 100 missions within a year. He flew all of his in just 10 months.

“I’ve lived a life that’s a lot more dangerous than the odds of an earthquake,” he says.

Morgan recalls the sound of earthquakes from his childhood and says it reminds him of trains he heard while flattening pennies on tracks with his brother. One day, they were digging a trench in the backyard when an earthquake hit, shaking the very ground they were digging up.

Still, he says earthquakes have rarely been raised as a topic of conversation among friends or family throughout his many years here. “To be honest, it’s just not a discussion that comes up,” he says.

If there’s anyone in Seattle who should be worried about an earthquake or a tsunami, or both, it’s Michael Langfield, the 55-year-old owner of the Bicycle Repair Shop. His store is directly across from the waterfront and tucked beneath the Alaskan Way Viaduct, a rickety raised highway that state engineers have said is almost sure to collapse if a major earthquake occurs.

Still, Langfield is unmoved. He points to the freight elevator to his left, which he believes will protect him from any direct blows, and gestures to thick wooden beams in the ceiling.

“If you look at those beams -- they’re not going anywhere,” he says. He loves his store’s location because ferry customers come across the street and into his shop, and it’s convenient for commuters to drop off their bikes in the morning for a tune-up.

“I feel safe -- but then again, I’m the king of denial,” he says. He says just a slight rise in the water level -- four feet, he estimates -- would flood his business. Even so, he says he doesn’t carry earthquake or tsunami insurance.

Langfield doesn’t have emergency supplies on hand at the shop.

“We don’t have a kit here,” he says, with a pause. “Maybe we should.”

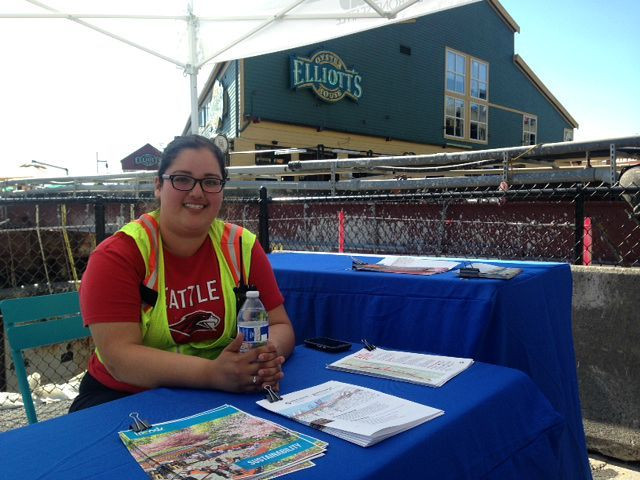

Those sorts of statements give Kiana Serna, who was handing out information about a seawall construction project along the waterfront, a sinking feeling. Serna is a 21-year-old park ambassador with the Metropolitan Improvement District and recent Seattle University graduate who majored in environmental science with a focus on urban studies.

“I don’t think people would actually be prepared for it,” she says. “It’s not something that you can really be prepared for.”

In one of her classes, she examined the most earthquake-prone neighborhoods in Seattle based on their history of landslides. Some of the most dangerous areas including Alki Point and Briarcliff seemed to also be some of the wealthiest, which surprised her.

“I think it’s not something people take into account when buying property or building,” she says. “Then again, it’s hard to make decisions just based on the possibilities of a natural disaster.”

To the extent that residents are concerned about a massive seismic event -- there is only so much they can really do to prepare for it. City planners and architects play the biggest role in protecting residents through ensuring the resiliency of Seattle’s building stock and infrastructure. To that end, the city is currently upgrading 600 buildings deemed most at risk.

Roach at Starbucks says all of her employees are briefed on an evacuation plan and told to lead customers to higher ground in the event of an earthquake. At home, she keeps an emergency kit with first-aid supplies and extra clothes, but says only three or four of her friends do the same.

“I feel like it always catches you off guard, no matter what,” she says.

Condon has insured the service equipment in his coffee shop in SeaTac, but hasn’t purchased earthquake insurance for his business or home -- even though his wife has tried to talk him into it. He’s counting on a different kind of insurance -- figuring that if a terrible earthquake does hit the region, federal aid will flow in.

“I don't even have an earthquake preparedness kit,” he says. “That's how much I worry about it.”

Condon and his wife plan to retire to Idaho soon, but the move has nothing to do with eluding the big one.

Both Langfield and Morgan say the biggest risk facing the region is not an earthquake, but an eruption. Mount Rainier, an imposing snow-covered volcano, is easily visible from throughout Seattle, and the simmering underground supervolcano in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming could erupt at any moment.

They are both far more concerned about those two volcanoes than the potential for an earthquake.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.