Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): A Trade Agreement You Should Care About

A comprehensive Asia-Pacific free trade deal is still on track to cross the finish line by year's end despite a daunting list of unresolved issues and U.S. President Barack Obama's absence from a regional summit that is ironing out differences on the pact.

The three-year-old Trans-Pacific Partnership talks, now involving 12 nations, are aimed at lowering trade barriers across a wide range of sectors in 12 Pacific Rim counties that would stretch from U.S. to New Zealand and from Japan to Chile.

TPP, arguably the most important trade agreement in a generation, emerged following nearly a decade of disappointment in trade talks. The World Trade Organization’s Doha Development Round of talks first collapsed in 2003 and effectively died with the 2008 financial crisis. The death of Doha and the rise of TPP mark an important phase for global economic negotiations.

Here is what you need to know about TPP:

1. Why is it important?

If completed, the TPP would cover two-fifths of the world economy and one-third of interracial trade. It aims not just to eradicate tariffs on goods and services, but would cover labor and the environment, intellectual property, government procurement and state-owned enterprises.

Burgeoning global supply chains have been a significant boost to world trade in recent decades, strengthening the case for free trade zones. Increased internationalization and verticalization of production means that final goods now have a higher degree of foreign content. The International Monetary Fund reckons that the foreign content share in gross exports has, in effect, almost doubled in 40 years, according to Gustavo Reis, a senior international economist at BofA Merrill Lynch.

Moreover, the higher foreign content in final goods increases trade in intermediate goods. Trade in intermediate goods now accounts for more than two-thirds of global trade, blurring the boundaries of national trade interests by making international trade more intertwined. This expanded global supply network is one reason why there has been limited use of traditional protectionist measures in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

Both the U.S. and the Japanese administrations have embraced the project and consider it significant. “The TPP looks like a rare breed of an ambitious multilateral project with political backbone,” Reis said.

2. How involved is the U.S.?

The TPP is one of the main pillars of the Obama administration’s ambitious second-term trade agenda and is central to its plans for boosting America’s presence in Asia. In effect, the U.S. is leading the negotiations.

The TPP started out as a trade pact envisaged by Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. It was transformed in 2008 when the U.S. expressed its interest. Since then, the TPP has expanded to 12 members, bringing in Australia, Canada, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru and Vietnam. Japan -- often considered a free-trade laggard -- joined the negotiations this year, and South Korea is balancing pros and cons of membership.

The Japanese government has raised the TPP's profile by linking the trade deal to Abenomics -- the economic strategy aimed at pulling the country out of deflation.

3. Progress so far?

While leaders sound hopeful, there are signs the end-year deadline may not be met.

Obama was to lead talks at the APEC summit with the leaders of 12 nations negotiating the TPP agreement that the U.S. wants to complete this year. Instead, he canceled his trip in order to resolve the government shutdown in Washington.

The APEC meeting was a symbol of regional co-operation, but Obama’s no-show turned it into a symbol both of gridlocked politics in Washington and of the difficulties facing Obama’s commitment to refocus U.S. foreign policy on Asia.

“Obviously we prefer a U.S. government which is working to one which is not, and we prefer a U.S. president who is able to travel and fulfill his international duties to one who is preoccupied with his domestic preoccupation,” Lee Hsien Loong, prime minister of Singapore, a key U.S. ally and a member of the TPP, told business leaders at the APEC meeting, the Financial Times reports.

4. Winners and … participants

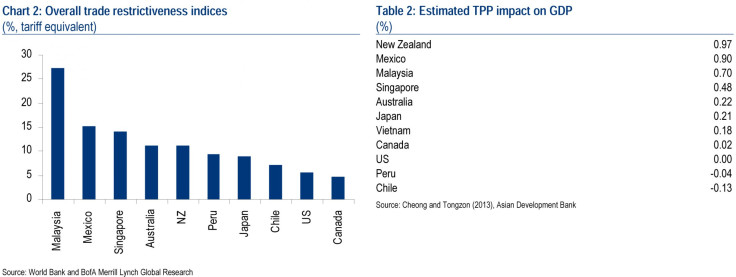

TPP members have very different levels of trade protection. Judging by the World Bank’s overall trade restrictiveness index, which measures the uniform tariff equivalent of a country's tariff and non-tariff trade barriers, Malaysia at 27 percent is significantly more insulated from trade competition than Canada at 5 percent. The benefits seem higher for a handful of the more protected economies, according to Reis.

The Asian Development Bank has estimated the impact of the TPP on gross domestic product and found that most member countries would experience moderate economic gains from joining the free-trade bloc. New Zealand, Mexico and Malaysia would likely benefit the most from a successful agreement. Singapore, Australia, Japan and Vietnam also stand to gain. In contrast, Peru and Chile are expected to be hurt. Both countries already have free-trade agreements with other TPP economies, so TPP could divert trade to competitors like Mexico and Vietnam, according to Reis.

Meanwhile, the lack of clear economic benefits for the U.S. does not seem to justify its engagement. But the U.S. sees the TPP as part of a foreign policy reengagement with East Asia. Critics of TPP negotiations have argued that the true U.S. goal is to contain rising Chinese influence in the region. China is not standing still, and is promoting a Sino-centric bloc, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership.

© Copyright IBTimes 2024. All rights reserved.